Morris’s Gudrun vs. 13th Century Gudrun

Presented to you by: Alexander Rzehak

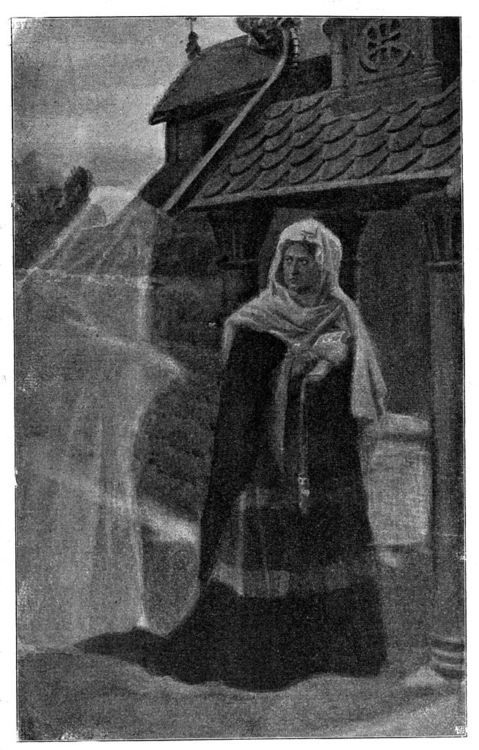

The Ghost of 13th century Gudrun

As time continues to pass, Morris’s depiction of a romanticized Gudrun becomes more and more accepted in modern society where Gudrun from the Saga of the Volsungs eventually will become forgotten. Her violent deeds have been replaced with piousness which were significantly more appealing to a Victorian audience and thus her original character will fade away. This image represents how Morris’s version of Gudrun becomes more appealing to modern audiences while her earlier rendition slowly fades away. This is similar to how Shakespeare’s plays overshadow the originals written by Plutarch. For example, Romeo and Juliet is known only to modern audiences as Shakespeare’s work and the majority have no clue who Plutarch even is. As time progresses, the 13th century Gudrun may fade completely away until only medieval scholars know the original story.

A Split Personality

William Morris’s “Sigurd the Volsung” depicts Gudrun in a very different manner than how she is portrayed in the original Saga of the Volsungs. Morris’s Gudrun is a tragic figure who must undergo the misfortune of losing her beloved Sigurd and is subjected to a life of misery as Atli’s wife. On the other hand, the Saga depicts Gudrun as a vengeful widow who is hellbent on exacting revenge upon whoever crosses her path. The dichotomization of this character that is created between the two texts is quite interesting and begs the question: why has Morris rewritten her in such a romantic way?

A Romantic Appeal

The most obvious answer to this is that the 13th century Saga of the Volsungs appealed to an almost ancient culture who glorified wrath and senseless bloodshed. In order to make his epic more palatable to the middle-class Victorian audience, Morris chose to omit many grotesque depictions of violence that could tarnish the image of epic heroism. Therefore, Gudrun never “killed her two sons” nor “had goblets made from their skulls” which were used to serve mead to King Atli (Saga 101). The striking imagery would have completely deterred audiences from being entertained, and the complexities of her character could not be accurately conveyed if that was the case. So, Morris’s artistic decision to exclude these details from his text allow a romantic reader to be more engaged with the story. Her character becomes more complex and relatable, for what Victorian reader could identify with this gore besides an executioner? Even Gunnar and Hogni’s deaths are minimalized. The lines describing the fact that “King Atli had Hogni’s heart cut out while he was still alive” and how “Atli had Gunnar thrown into the snake pit” were not included in Morris’ rendition (Saga 100). Rather, Morris elaborately wrote how their deaths “Rang sweet in the hall of the murder to make King Atli glad” in an effort to bolster the virtuous facade of Gudrun (Morris 302). In reality, she was simply reaping vengeance upon her brothers who had conspired to slay her husband Sigurd.[1] However, this too would stir uneasy feelings in the reader, and Morris’s decision to romanticize their deaths relieves any blame one could have for Gudrun. Effectively, rather than seeing a vengeful widow—a drastically unappealing figure in the Victorian period—the audience views her as a pitiful wife against the evils of the world. Yet violence is not completely absent in his tale, it is only deflected off of Gudrun and onto the surrounding cast. The dichotomization of innocence and violence creates an intriguing contrast within the story that drives the plot and immerses the reader within Morris’s fantasy. The violence that surrounds Gudrun makes her character all the more appealing. Even while I was reading Morris’s rendition, I found myself routing for her survival and luck. She is depicted as a hero, and a romantic hero is one that is surrounded by violence, not one who is consumed by it. Thus, this change was necessary to ensure the survival of his story over the course of time.

O What a Romantic Thing Fate is

The overarching theme within Morris’s epic is that those who love are fated to suffer which adds dimension to the minimalistic Saga of the Volsungs. None embody this theme better than Gudrun, which is why he chooses to end the poem with her. Her love for her dead husband, Sigurd, leads not only to the destruction of her blood brothers but also her house. Then, in turn, her love for them, which she can only feel once they have been slain, drive her to reap vengeance upon their murderer, King Atli. These events have been completely and utterly romanticized by Morris in order to retain his Victorian audience, as the Saga offers no mention of remorse or love but only details the gruesome events that occur. Even the arson committed by Gudrun is twisted to fit his agenda. The line which once read, “Then they spread fire in the hall, and the people inside burned to death,” was twisted in order to depict the coming of Ragnarok by Gudrun’s hand (Saga 101). To push this imagery, Morris writes:

“She spake; and the sun clomb over the Eastland mountains’ rim

And shone through the door of Atli and the smokey hall and dim,

But the fire roared up against him, and the smoke-cloud rolled aloof…

The gold and the sea-born purple shrank up in a moment of space,

And the walls of Atli trembled, and the ancient golden place.”

(Morris 304-305)

By choosing to conclude the epic in such a way, he offers a parallel between Gudrun and Loki, for just as the god of mischief causes Ragnarok, she ignites the conflagration which consumes both the heroic world and the gods themselves.[1] The final scene once again returns to romanticism as Morris writes, “O Sea, I stand before thee; and I who was Sigurd’s wife! By his brightness unforgotten I bid thee deliver my life” (Morris 306). This scene is very appetizing to Victorian readers for it emulates the classic Shakespearean play ending, however, he once again strays from the original text. A reigning trope in all of Shakespeare’s work was suicide. We see this theme in plays such as Antony and Cleopatra, Julius Caesar, Romeo and Juliet, and so forth. Audiences gawked at these dramatic scenes for their beloved character has been consumed by their respective plights. Ending a character arc in this way also serves a different purpose—it rights the wrongs previously committed by that person—it demonstrates honor. For example, Brutus kill himself after realizing his actions harmed Rome, yet he was honored by all, even by his enemy Octavius. Morris’s decision to end his adaptation in this way may have been influenced by Shakespeare’s stories to gain dramatic effect, for he chooses to cut the story off with Gudrun’s plunge into the sea and forgoes her survival and eventual third marriage to King Jonak. In addition, by killing her off in an ‘honorable’ suicide, it is possible he is trying to right the wrongs done by her character in the Saga of the Volsungs.

What Is Right?

Morris’s adaptation of the Saga of the Volsungs strays from the excessive violence that was customary during the 13th century and instead tailored his epic to fit a more modern audience. While the storyline is essentially the same, the ways it is portrayed are completely divergent as both versions align with different underlying themes. The romanticism of “Sigurd the Volsung” may be a primary reason for Morris’s success, but this came at the cost of significantly editing the original to convey new meaning. As a result, Gudrun’s character loses all maliciousness and is instead portrayed as the most tragic hero in the epic.

[1] https://norse-mythology.org/gods-and-creatures/the-aesir-gods-and-goddesses/loki/