The Superficiality of “The Lady of Shalott”

by Emily Baldo

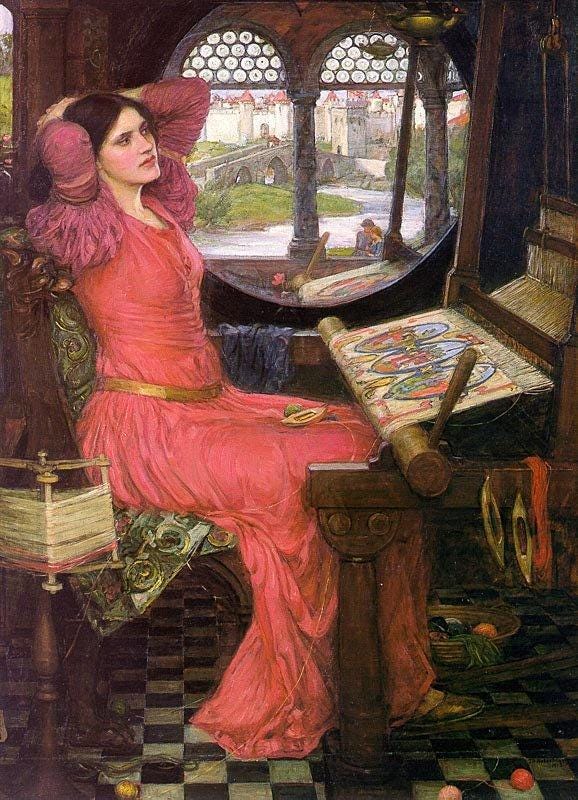

A class discussion in Victorian Medievalism focused on the curse that plagues the Lady of Shalott, and the way she must gaze through a reflection to see the outdoors. While I am not dismissing the heartbreaking aspect of her story, the contentedness she appears to feel as she weaves her days away in her tower, singing and passing the time, I would argue that the last section of the poem demonstrates the sort of superficiality that is only really present in medieval tales of courtly love.

Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” concerns a woman who remains unnamed to readers, cursed to watch the world through a mirror. As far as we know, she has never sought a way around this curse, or a way out of her tower, until Lancelot happened by, singing with the knights in his company. Immediately taken by his appearance, she is desperate to reach him for- one look? To exchange a few words? It is unclear exactly what the Lady hopes to accomplish in the little time she will be granted by the curse, but her appreciation of Lancelot’s handsome face and apparent good humor tempt her enough to throw away the safety of her tower and seek out the realness, not the reflection, of the world.

It is worth noting, too, that although Lancelot never lays eyes on her while she is alive, in his only sentence he speaks about her, he says: “‘She has a lovely face’” (l. 169). The superficiality of their encounter, both what prompts it and what closes it, stood out to me. This was my second reading of the poem, and with the themes of courtly love in mind and the way the love for appearance take precedence, I couldn’t help but relate the Lady of Shalott’s story to those motifs. The Lady of Shalott can certainly be read as a strong female character, who seizes her chance to take what she wants and to break her curse, taking death by the reins rather than continue to sit by her mirror and watch others live to the fullest, but the undertones of obsession with beauty and, almost, male attention, taints this interpretation a bit. Yes, a man was technically the cause of her demise, but he was also the first thing she considered worth the price of her life, and this certainly prompts further thought about Tennyson’s poem.