Gudrun in The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and The Saga of the Volsungs

By Maggie Martone.

Recently I had read William Morris’ The Story of Sigurd the Volsung, and I can’t help but notice the many liberties the work takes from its original source material, The Saga of the Volsungs. One portion of the original I found to be particularly interesting yet disturbing was “The Conversation between Atli and Gudrun”. Morris’ version of this section is called “The Ending of Gudrun” and despite the few shared qualities, I liked his version much more. I did not find myself liking the character of Gudrun with my initial read of The Saga of the Volsungs, despite how much I wanted to. I know it’s likely that most of the narrative’s audience would be in support of her as she seems like a total badass. Serving justice in the form of revenge is a narrative that many people could get behind, but I also realize I must be one of many who is hesitant to root for her, especially with that child killing part leaving a bad taste in (hopefully) all of our mouths. I don’t completely blame Atli when he says “’Cruel you are to murder your sons and give me their flesh to eat. … Your monstrous deed is unparalleled in the memories of men.’” Though this may not have been the intention of the author, our attention is drawn to her womanhood with this statement as he deems her actions being the worst that any man can recall.

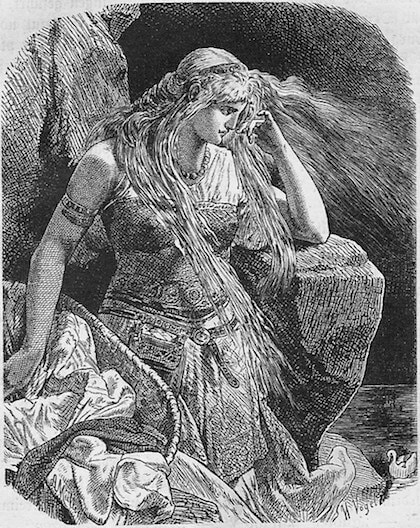

But then he continues, “’There is much lack of wisdom in such brutality. It is fitting for you to be stoned to death and burned on a pyre’” (pg. 104). He insults her intelligence here, showing the time periods general thoughts on women. He even says she is deserving of a death we may recognize as one fit for a “witch”. I become more certain that this attack on her intelligence was one common for women since it is so completely out of place as Gudrun’s plan worked perfectly. The Story of Sigurd the Volsung changes my perspective of this character almost entirely. There seems to be more depth to her overall with the detail Morris provides. Her entrance into the feast is depicted as follows, “There she goes in that wonder of houses when the high-tide of Atli is dight, / And her face is as fair as the sea, and her eyen are glittering bright” (pg. 302). Right away she is given a certain majesty we don’t get from the original text and the rhythmic flow emphasizes this description with grace. I appreciate this description all the more knowing the bloodied events that are to come. The action of both narratives is also somewhat different as there is (luckily) no child cannibalism this time around! Gudrun also successfully commits suicide at the end of Morris’ work instead of surviving and becoming the wife of King Jonakr like what was told in The Saga of the Volsungs (image pictured above). This to me feels like a more satisfying ending as she is no longer used simply as a lover, wife, or a mother to children. Gudrun decides her own fate, one free of Atli. She also does not promise him an extravagant funeral like he had requested within the source material. She has lost everything, and it feels a fitting end to a narrative that is already full of sadness and gore. Overall, this slightly more positive depiction of Gudrun is rather ironic as the Victorian period in which Morris wrote his work was one of misogyny and suppression while the 13th century was nearly the opposite as women held many social liberties and rights.